Why can't regression models perform classification?

You might’ve noticed that logistic regression is more often than not used as a classifier. Then why can’t I use linear regression as a classifier? This is a question many of us have asked ourselves when first learning about the two models, and probably take for granted. But the answer is not as simple as it may seem, and is a great lesson in what makes a model a classifier in the first place.

What is a regressor? What is a classifier?

A regressor is a model that predicts a quantity, specifically some real number \(x \in \mathbf{R}\). A classifier, on the other hand, outputs a class, essentially outputting a vector that is typically argmax’d. They are the two standard approaches to supervised learning, and are well-known to anyone who does ML.

What allows a regressor to be used as a classifier?

It’s commonly thought that logistic regression works as classification due to using a decision rule. It seems to be a good classifier if you give it a decision rule like below.

\[a \ \ \text{if} \ \ y >= 0.5 \ \ \text{else} \ \ b\]However, the real reason logistic regression is well-suited as a classifier is because its predictions are interpreted as the conditional probabilities \(P(y = 1 \mid x)\). That way, you can model it as the likelihood that \(x_i\) belongs to class \(A\). If it’s low enough, you can decide it belongs to class \(B\) instead if the probability is low. This leads people to adopting the decision rule above, but you can set whatever threshold value you want. If I’m deciding who to bet on to win a race, and some bookie tells me there’s a 25% chance racer \(A\) wins the race, I can decide to put him in the “not going to win the race” category, but that’s because I chose 25% as at or below my decision threshold. I could choose my threshold to be 10% and therefore declare that racer \(A\) will win the race. It’s up to me.

A logit function is also unlike \(n\)th-degree polynomial regressors, however, in that its range is restricted from \(0\) to \(1\). This might clue you into the fact that polynomial regressors do not consider predictions conditional probabilities, and can therefore output any real number. You can’t interpret their results as probabilities of the input belonging to a class. This makes interpreting its output problematic and nebulous, only going off of a decision boundary for the scores and having to change the boundary itself after any new point is introduced into training.

Using a linear regression as a classifier anyway..

Suppose I go against the grain and try and force linear regression to work for classification anyway. Andrew Ng has a lovely course which highlights this issue with a few graphics that I’ll use here.

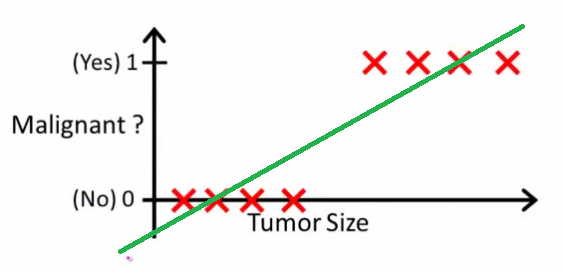

Let’s say I am trying to predict whether someone has a malignant tumor or not depending on its size, and try to fit a linear regressor to it to classify whether it’s malignant or not. Let’s say I took some of the data, and tried to fit it.

Well, that looks pretty good! I could probably decide on a decision boundary at like 0.5 or something and use this!

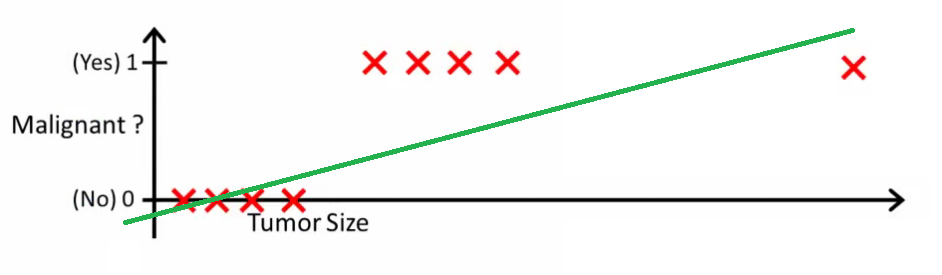

Suppose, however, I add another datapoint from the training set, a sample with a far larger tumor size, and fit it again.

The 0.5 decision rule is completely ruined now, which means after every sample my decision rule would have to change. This decision rule should be used to predict an unseen datapoint, not redefined by it. It’s not uncommon for models to be initially trained on a smaller dataset, and then trained on a larger one when more data is acquired, which would make dealing with this kind of model exhausting.

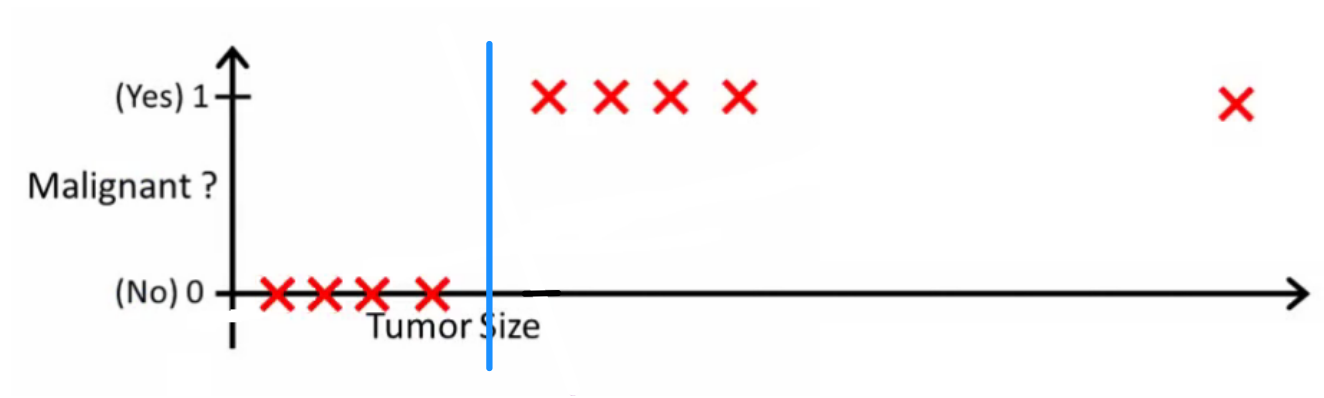

Ultimately, a thing you might have heard of is the perfect classifier, \(\bar f\), like below:

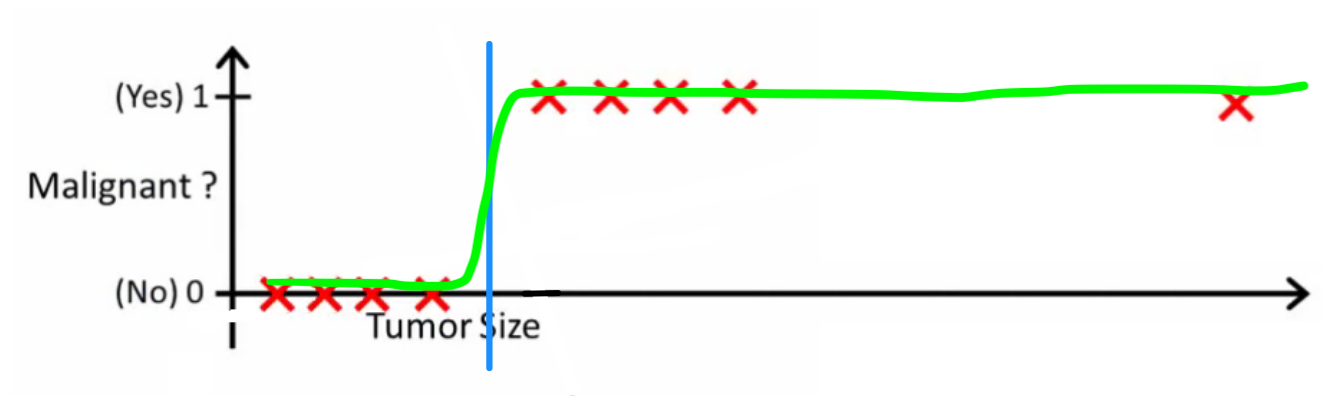

which has zero classification error. The goal of classification in cases with this level of complexity is to create a model that is as close to \(\bar f\) as possible. A logistic function actually approximates this quite nicely, and far nicer than linear regression.

As you can see, I have very scientifically drawn it on.

Caveats and other notes

That being said, with some constraints to ensure points don’t exist near the boundary, linear regression can work. See an example from whuber’s answer here.

I also wanted to add that I especially enjoyed learning about the logit well-approximating a perfect classifier, because it reminds me of another sigmoid modeling a step function that is bounded at a range of \(0\) and \(1\), the Fermi-Dirac distribution. As the absolute temperature converges to \(0\) your sigmoid reduces to a step function.